If COVID-19 has taught us anything it is that our ‘business as usual’ model has failed us all. It has exacerbated our crisis because it allowed us to ignore 3 critical societal truths. Conducting business as usual required many of us to silence our voices from speaking out on these truths. That’s how business as usual in America has always worked: it trades your silence for a lifestyle of misguided privilege to a few. Had we confronted and responded to our truths earlier on as a nation, we could have shifted our country’s trajectory towards COVID-19. 1. We have always had vulnerable individuals and traditionally repressed communities in need of our collective compassion and attention. We have always known the truth that members of traditionally repressed communities suffer from health conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, and high blood pressure at a disportionate rate than their white counterparts. These health conditions among the Black and Latinx communities are exacerbated by the difficulty these communities face when trying to access consistent and intentional healthcare. As a result of our failure to adequately mitigate the healthcare discrepancies faced by traditionally repressed communities over the years, COVID-19 has taken an irrevocable toll on both the Black and Latinx communities. Ibram X. Kendi poignantly articulates the numeric impact for repressed communities in What the Racial Data Show. 2. We have always had families living from paycheck to paycheck. Roughly speaking, COVID-19 hit our country in January of this year. Exactly one year prior to the month, Zach Friedman wrote a piece in Forbes Magazine entitled, 78% Of Workers Live Paycheck To Paycheck. Living paycheck to paycheck means just what it implies: that folks can only (and barely) afford to pay their expenses with the income they receive --- leaving little to no wiggle room for thriving and enjoying life. Unable to set aside savings for a ‘rainy day’, many Americans were (and continue to be) ill-prepared to weather the tumultuous downpour of financial woes associated with COVID-19. 3. We simply cannot afford a return to business as usual. The current “business as usual” social systems in America are constructed such that it accelerates access to resources (i.e. mental and physical health care, education, jobs, housing) for some, at the expense of diminishing access to those same resources for others. Returning to a state of being, and conducting ourselves as if a global pandemic did not just happen in our lifetime is not an option. All of what we are experiencing physically, emotionally, and mentally from COVID-19 will be for nothing if we do not, as a country, emerge from this period with a new vision and version of business as usual for America. What we must persist towards is a business path where people and communities are put first and over profit. Admittedly, trepidation comes with not knowing exactly what an alternative to “business as usual" would look like. And yet, our survival depends on us figuring out how to co-create another way. The truth is that we see glimpses of another way all around us, as we literally sit in the midst of our crisis. We see it when grocery stores create hours of operation that hold space exclusively for the most vulnerable in our communities, including senior citizens. We see a glimmer of another way when businesses limit the amount of goods an individual can buy so that more members of our community can have access to the goods, services, and resources they need. Portions of a new way is unveiled within the public discourse and potential actions to implement more options for employers to engage in remote work. We even see the emergence of a new model of business as usual in the amplified voices calling for student debt to be forgiven. These are all glimmers of what is possible, brief confirmations that we have the capacity to operate from human decency and dignity. If we persist, we have the ability to create a ‘business as usual’ for our country where we are no longer driven by fear and scarcity, but are able to thrive and live from a place of courage and abundance.

1 Comment

Photo Credit: @angelinabambina

While many organizations are engaged in cultivating social justice out in the world, they are simultaneously struggling with how best to address the multiple layers of internal injustices that create unwelcoming work environments, particularly for black, indigenous, and people of color (BIPoC). This past August, Portland Women in Technology (PDXWiT) published the 2019 State of the Community. The report offered findings from a survey of just over five thousand respondents in the tech world for the purpose of gauging the sector’s health when it comes to matters of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). One of the most fascinating realizations that emerged from the study is that: “most white people in the industry said their companies take diversity seriously and would recommend someone from an underrepresented group work at their company. But among people from other racial and ethnic groups, and transgender people, fewer than a third agree…” To this discovery, Megan Bigelow, the board president of PDXWiT stated: “These [DEI] initiatives that are being built are resonating with white people. However, the efforts of the white people who generally run those companies aren’t resonating with the people they say they’re trying to reach…” Demonstrating this same dilemma within the business sector, despite the goal of creating an economy that is inclusive of everyone and implementing a new model of inclusive corporate governance, Jay Coen Gilbert, cofounder of B Lab explained in Erasing Institutional Bias: How to Create Systemic Change for Organizational Inclusion: “…only 43 percent of B Lab’s staff who are people of color feel they can bring their whole selves to work, compared to 96 percent of their white coworkers. Houston, we have a problem..” Jay is absolutely right —we do indeed have a problem. However, what both Megan and Jay describe is not the actual problem. The facts that diversity initiatives are not resonating with BIPoC, and they do not feel like they can bring their whole selves into a work space are symptoms of a deeply entrenched problem within organizations. The problem organizations are faced with in their attempts to cultivate just, equitable, and diverse working environments is that they are not relying upon the innate wisdom and leadership that can be found in the voices that have been most acutely impacted by unwelcoming, inequitable, and exclusionary spaces. Simply put, organizations are not placing the appropriate focus on the voices of black, indigenous, and womxn of color (BIWoC) when trying to create transformative organizational change. And, beyond the appropriate focus, few organizations are consistent with following the lead and directives of BIWoC. The word “womxn” includes those who are both members of traditionally oppressed racial/ethnic groups and who identify as trans, gender non-conforming, non-binary, or cisgender. The well intentioned landscape of organizations is peppered with examples of conversations and actions around DEI by well-meaning, predominantly white-led nonprofit organizations. To the detriment of these organizations, such initiatives are overwhelmingly anchored around the bravado of the white voice. The irony here is that at the same time organizations are amplifying the call to cultivate diversity, equity, and inclusion in their workspaces, the voices that matter most in answering this call are (still) being muted and silenced. In Hacking Diversity in Tech by Emphasizing Retention, Megan Rose Dickey posits that retention is key in helping to cultivate diversity. What is intriguing in this piece is the use of the word hack as a way to communicate that there is indeed a “work around” for the problematic environments organizations are grappling with. By definition, a hacker is any skilled expert that uses their knowledge to overcome a problem. If the problem is the lack of diversity -- as Dickey’s article suggests, and this lack is a direct result of the systemic marginalization that occurs within organizations, then there is no better expert voice to hack diversity than those who most acutely suffer from, and bear the brunt of the problem. It goes without saying that white folks ought not be the experts in the room on this because they do suffer the most from the problem. Yes, white folks suffer within the oppressive system that we aptly name white supremacy/white patriarchy. However, the suffering is acutely and vastly different than the suffering that is experienced by BIWoC within the same system. In fact, I would go as far as to say that while they do suffer, white folks are beneficiaries of the problem, which is the very reason why they are able to be seen as the experts in an area that fundamentally is about addressing the oppression on traditionally impacted populations. What organizations lose in silencing and muting the already marginalized voices of BIWoC is the lived experiences and narratives of BIWoC who have been at the painful end of systemic marginalization in organizations. When organizations choose not to center BIWoC voices in creating just and sustainable work environments, they end up reducing critical narratives and stripping away the profundity that is deeply embedded in these narratives. In doing so, organizations forfeit access to the groundswell of wisdom that is only found within the years of experience BIWoC have in both navigating and surviving unwelcoming and exclusionary organizational environments. For organizations working to better hold DEI within their work spaces, success will be achieved to the extent to which they are able to shift power to the voices and lived experiences of BIWoC. When we consider the role marginalized and impacted people play in creating transformative organizational change, it has been said that it is the very living, existing, and survival of the marginalized that is the key. If we can agree on this belief, then organizations must remember that it is precisely the marginalized position of BIWoC that renders them uniquely suited and poised to create meaningful organizational change when it comes to creating spaces that better hold and support diversity, equity, and inclusion. As organizations further marginalize, mute, and silence the voices and resourceful power that lies exclusively within BIWoC, efforts to create diverse, inclusive, and equitable work spaces will only end up perpetuating the very harmful environments they desire to transform. Mother. Teacher. Agitator. S. Rae Peoples is the founder and principal consultant of Red Lotus Consulting. She enjoys spending her time in meaningful relationships and work that supports her desire to promote justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion. A native of California with a Midwest upbringing, S. Rae is currently rooted in motherhood and community while serving as a student affairs administrator at Massachusetts College of Art & Design in Boston, MA.  Photo: Courtesy of Christian Magazine Diversity can, in fact, be sharpened as a double-edged sword that is quite often masterfully and strategically used, particularly by white-led organizations. One sharp edge of the sword is quite frankly the commodification of diversity. This inflicts a particularly deep and painful wound on black people in particular because it enables [white-led] organizations to make money literally off the backs of our bodies --- as commodification of the black body was at the core of slavery. Nowadays, commodification of traditionally oppressed bodies is repackaged under “diversity”: a package label that not only is politically acceptable but is in fact considered a label in progressive movements towards racial and social justice. Diversity is a “feel good” label. And when organizations can tout this feel good label at presentations, fundraising events, churches, schools, and on grant applications, --- the money flows to the “great work” these organizations profess to be doing. And there it is. Commodification. Money being generated off the presence (or backs) of black and brown bodies. The other edge of this sword is optics. More often than not, organizations use diversity as a concealer, working overtime to gather and plop black and brown bodies in its environment while not addressing the environmental aspects that does not make existing in a black or brown body sustainable within the organization. The overriding issue with diversity as it is held by most organizations is that it emboldens an organization to shout, “look at us, we’re good because we’re diverse!” while not engaging in any personal work to examine how one may actually be playing an active or complicit role in perpetuating a harmful working environment for black and brown employees. As a result, diversity is then used to hide the ways in which whiteness is internally and systemically embedded in the organization’s DNA. While there is a tendency to conflate whiteness with the racial identity of white people, I hold a clear distinction between the two. When I use the term whiteness I am referring to a tool used to sustain white supremacy. It is characterized by unexamined privilege; an often unconscious perception of being white as the norm, and being a person of color is other than normal; and silence or acute discomfort with interrogating systems, policies, culture and relationships through a racial lens. The truth of the matter is that anyone can wield the tool of whiteness. However, the harm done by whiteness hits different on black and brown bodies when it is used by white people. This summer, I served as the Director of Operations for a summer camp that worked to develop leadership skills in young girls. Camp was held at a naturally picturesque college which is nestled in a vibrant urban neighborhood and has a longstanding tradition and legacy of playing an active role in racial and social justice. Our Summer staff started out with a team of 12 women: most of whom identified as Black/WoC and Queer. From our collective team experience, there emerged 3 critical lessons that highlight the ways in which diversity is being inappropriately held in our modern movements towards racial and social justice. Lesson 1: Diversity Does Not Mean “All Are Welcome” As both a staff member and resident of the host city for camp, I walked into the camp experience with the naive notion that campers and families would adequately reflect and represent both the racial and socioeconomic diversity of my city. Like several of my colleagues, I held this notion primarily because it is a reasonable assumption that an organization would reflect the population of the city/region it is operating within, particularly when it espouses to take up space in a way that honors diversity. According to the 2018 Census, the host city is roughly 36% white, 27% Hispanic/Latinx, 24% Black/African-American, 16% Asian, and 7% who identify as multi-racial. From a socio-economic perspective, from 2013-2017, the median income was $63,251, the per capita income was $37,256. On average, there were 3 members in a household. The average rent in the host city last year was around $2,500. Tuition for camp ranged between $2,700-$3,700. The organization provided financial aid. It was unclear as to the number of recipients of such aid. Ultimately, the data provides clarity relative to the difficulty with which the average girl living within the host city limits would be able to access and experience camp being offered in their own city. Within the first few days of camp starting, black staff members began to have a gut-wrenching feeling that the environment was not welcoming for them. During a staff meeting, a black woman asserted, “this is not a safe space for black women and girls to heal.” What was heard and understood as a defensive rebuke of the assertion by their supervisor was, “that’s not what this space is for...what about Latinx girls, other brown girls, Asian girls, girls who are LGBTQIA...” This statement aggressively pulled at the strings of trust between staff and their leader, unravelling their feelings of being seen and welcomed in the organization. As a result, within a month of a camp program that is only 6 weeks long, the organization hemorrhaged 25% of its summer camp staff, all of whom were black women. Simultaneously witnessing and bearing the brunt of whiteness was difficult for staff members. One word used by a woman of color staff member during a meeting to describe how she felt was simply “bamboozled.” A personal demonstration of the culture of whiteness within the organization is seen in the following email exchange between me -- black staff member (BW) and a white mother (WW): WW: Attached are 2 documents...so that I don’t have to type it all into the system... BW: So that I have clarity, is there an extraneous reason as to why this is just now being turned in?... WW: Because I’m extremely busy with work and life generally...do I need to cc the CEO of the organization? I served on the board for 6 years and do expect a little more respect. WW: And just to be extra crystal clear... I brought tens of thousands of dollars to the organization, so if this is how I will be treated going forward I will re- think how I support the organization... BW (c c-ied CEO, COO, COP, and Director of Summer Programs): Your responses are highly offensive. Regardless of where you think you sit. How you think you sit, and how much money you have generated for this organization, your words are not only hurtful, but profoundly and dangerously rooted in a level of white privilege that I simply will not tolerate. Much like the organization I worked for this summer, many organizations (particularly white-led organizations) are well-intentioned in stepping into the good work of diversity, equity, and inclusion. However, my point here is to amplify the fact that not enough white people (and leaders of these organizations) are talking about the ways in which white people continue to center whiteness within that good work. Lesson 2: Diversity Does Not Absolve An Organization From Pausing To Interrogate The Impact of Its Decisions, Actions and Objectives On any given day, campers would ask to touch the hair of black women or call them “Auntie.” Black staff were asked by white girls to fold or clean their clothes. To add another layer of harm, a camper was observed engaging in a highly egregious act towards two black women who were members of the college community — which ultimately played a role in the decision to send said camper home from camp early. These instances of whiteness gave a general sense among black women in the space that their time and presence was being used to serve as ad hoc mammies of predominantly white girls. Girls who were coming into the space with an intense generational legacy of whiteness. Despite the downward spiral the staff was experiencing, the organization chose not to pause. Instead of finishing Session 2 and electing not to go through with its final session -- at the time of my writing this piece, the organization was gearing up for Session 3, choosing to push towards and through its last 2 weeks. On face, it is understandable that an organization would want to persevere and push through the last 14 days of a program. However, given the fact that by the end of Session 2, several black women left the team (1 due to a stress-induced illness, and 2 due to no longer being willing to remain in an environment that did not honor them) and many staff members expressing varying levels of suffering, the decision to continue was deeply dismissive of the relationship between the organization and its summer staff. The night I decided to leave the team, the COO asked me what it would take for me to stay and help out with closing day for Session 2. To her question, I responded, “Cancel Session 3 and honor the full contract of all summer staff members”. Contemplating my request, the COO stated that the organization would lose money on the facility it paid for to hold camp and that it would have to refund money to those who were planning to attend Session 3. As a result -- from the organization’s perspective, honoring my request was not financially responsible. Acknowledging the fact that the organization would have had to absorb a significant price in pausing Session 3, the monetary price pales in comparison to the internal price summer staff had to absorb in being placed in a painfully stressful working/living environment. In ultimately placing a summer camp program and the monetary cost of it over the bodies and wellbeing of women being directly and negatively impacted by their choice, the organization placed higher allegiance to money and ego over the hurt-filled lived experiences of camp staff members. This is the commodification of diversity in action. Interestingly, the organization prides itself on the notion of women and girls being “all kinds of powerful.” The irony with this is that the choice of the organization to place anything over the value of the lived experiences of women in general, and black women in particular who staffed the camp program, was the weakest and most perverse display of feminine power. Lesson 3: Diversity Does Not Shift Power Reflecting on my summer camp experience, the equation that I think best describes how harm is exacted if diversity is not appropriately held is: Diversity - Power Shifts + Capitalism & Ego = The Status Quo of Hurt, Harm and Suffering From Whiteness As a society, we are focusing on the wrong point in our quest to create and manifest racial and social justice. We are placing our attention and intentions on the wrong piece of the equation in our attempt to create a better world. And here’s why: Diversity just is. It is already existing. We do not have to create it. Diversity is literally all within and around us. However, diversity will not be properly held and honored if the power dynamics remains out of balance and skewed to the advantage of white people. It is a pivotal aspect of the ultimate goal of moving all of us towards confidently engaging in the continuous and tedious work to restore balance in how power is understood and held within relationships. Shifting power allows each of us to simultaneously take up space and create the space required to hold all of who we are and the diverse dimensions each of our whole selves hold. Diversity without any shift in power is the point at which we inflict harm on one another in the name of diversity. A couple of weeks ago, I facilitated a community conversation and workshop in a city that is near and dear to my heart: Oakland, CA. Oakland is home for me. It holds my community of support; it has my absolute favorite coffee shop: and it holds several close friends that I now call "family." My strategy for entering and working towards racial justice and abolishing white supremacy has always been a think globally, act locally approach. I consider it my love offering to my community to dedicate my time, energy, sweat, and tears to cultivating racial justice right here at home: in the Dimond District in Oakland, CA. All of the participants for the workshop (what I lovingly refer to as "the collective") identify as white cis women, and what follows is a brief reflection of observations, thoughts, and realizations that arose for the collective as I guided them through conversations, journaling, and group exercises in the workshop topics of disarm, divest, and dismantle. Disarm:

Divest:

Dismantle:

Reflections from the collective is a mirror the exposes parts of all of us. Particularly for the white community, what emerged in this workshop for the collective are indeed the very churnings, thoughts, feelings, and knowings that so many other white people must be carrying inside and grappling with themselves. A wise teacher I admire immensely often shares:

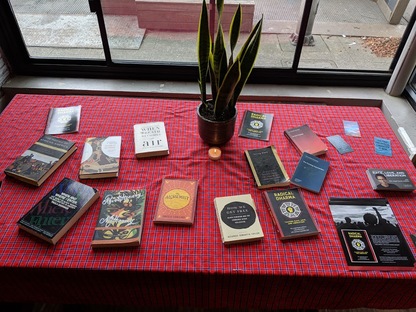

"when we give ourselves permission to feel and hold all of who we are, all of our identities -- when we give ourselves permission to NOT leave any parts of us behind, we give others permission to do the same for themselves." In that statement is both a simple and urgent invitation for you. I invite you to engage in spaces and conversations that will extend to you the permission to discover, embrace, and bring all of who you are into the work of racial justice. If like me, you are wondering what would emerge for you and your community on the topics of disarming, divesting and dismantling toxic systems for racial justice, let's connect, chat, and conspire to offer this workshop in your neck of the woods. The truth is that we need you and your community in the pursuit for racial justice, but we are going to need your whole true selves to make any sustainable gains in our audacious movement. Join us. Completely. This past weekend, I had the good fortune of participating in Centering Leadership in Presence. This program is an encounter designed specifically for women wanting to step more fully into their innate power to affect change, the space was held by Rev. angel Kyodo williams at Omega Institute. The opportunity to center my leadership and lean all the way into my powerful feminine energy in the spring beauty of upstate New York was literally a breath of fresh air.

POWER REDEFINED, REIMAGINED, & REDIRECTED In our society, we are pretty much force fed the notion that there is somehow a limited supply of power. And because of the perceived scarcity of power, we exist in spaces which communicate (to women in particular) that we have to work our ass off and bend and contort ourselves so that we can be seen as valuable or worth having power being bestowed upon them. One of the most important lesson I received form Centering Leadership in Presence is that the way in which our culture would have us to define and believe the way power works is completely absurd. It has become clear to me that this absurdity is intentionally designed to sustain an imbalanced power structure primarily within ourselves as women. The internal turmoil women experience within an imbalanced power structure results in an interruption in access to the divine-given power women already possess by virtue of our existence. And it is this constant interruption to access to this resource that severely impacts the way women are seen and heard in the home, in schools, in houses of worship, and in professional spaces. To counter the traditional and unsustainable way we are taught to think about power, Rev. Angel offered four simple, yet mind shattering truths during the program:

GROUNDING MY POWER TO WHAT MATTERS (TO ME) My time at Omega Institute and participating in Centering Leadership in Presence graciously invited me to drop myself into and reconnect to what matters to me. Not what matters to my son. Not what matters to my mother or my pets. Not what matters to my community. Being in this retreat gave me the space and time I needed to re-member soul to what truly matters to me. And the moment I reconnected to what matters, I felt a renewed and intense level of energy and purpose. To embody and extend pure unadulterated, unapologetic powerful love is all that matters to me. This is all the “true north” I will ever need to tap into, and release all of this here Black Girl Magic that is my innate power. My invitation to all of my mothers, aunties, and sisters wanting to show up in their lives fully in their power: my invitation to each of you is that you commit to taking the time to re-member to what matters to you, tap into that source, and release all of your beautiful power in a world that so desperately needs it. By S. Rae Peoples

Originally posted on LinkedIn on February 13, 2015 This is how in one song, an influential musical artist like Beyoncé can propel the feminist movement forward by leaps and bounds, only to, in one fell swoop of another song, knock all of creation back to nearly the dark ages of gender (in)equality: Over this week, the media has been all abuzz with reactions to Beyoncé’s performance of “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” at the 2015 Grammy Awards. At first glance, the situation is just something to chalk up to the nuances and craziness of show business. But when you really start to look at how it all played out, this “minor” nuance becomes one gigantic smack clear across the face of feminism. This realization is surprising, considering that Beyoncé is such a prolific feminist, who with one song lasting less than five minutes, singlehandedly catapulted the word, “feminist”, and it’s meaning into public discourse. In fact, it is in this very song that the insights from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “We Should All Be Feminists” speech is so tastefully highlighted. So, let’s reassess the Grammy’s brewhaha against the backdrop of additional excerpts of Adichie’s speech, and the core purpose of the movie Selma: Background Ledisi, an accomplished musical artist in her own right, plays the character of Mahalia Jackson in Selma. Performing within this role, Ledisi sings a beautiful, hair-raising on your arm, back and neck rendition of “Take My Hand, Precious Lord.” So far, so good. No foul, no harm...until... The Grammy’s Want Ledisi The powers that be wanted “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” performed at the Grammy’s. Now, at this point, it is reasonable to assume that Ledisi should, and would be performing the song since she was the one to sing it in the movie. However, at some point in the planning process, Ledisi was out, and Beyoncé was in. According John Legend, during his interview with ET: “We were actually approached by Beyoncé. She wanted to do an intro to our performance and introduce us…you don’t really say no to Beyoncé if she asks to perform with you." Here’s the issue with a response of “you don’t say no to Beyoncé”: That answer is just mindboggling, especially given the fact that John Legend took part in, and has received awards for a movie about a movement that, in the face of wrong, was all about saying no. In fact, it would be safe to say that the very reason for the majority of Mr. Legend’s performances this year was due to his work in a film that revolved around standing up for what’s right. If Beyoncé made such an inconsiderate request, then just purely on a human decency, common courtesy, what about the golden rule level, the proposition was wrong. There was a perfect opportunity to “practice what you preach” (or act out on screen) for Mr. Legend. Alas, the opportunity was sorely missed. Ledisi’s “Graceful and Classy” Reaction Ledisi is just as surprised as the rest of us upon realizing that she wouldn’t be performing her song from Selma. In the face of this blatant affront, Ledisi has been praised for her reaction with phrases like, “she’s taken the high road” and “she’s disappointed but not upset.” This kind of praise presents the notion that feelings of anger in this situation is not okay. It ignorantly implies that by stating her true feelings, Ledisi would not be taking the high road- because the high road (wherever the hell that is) does not involve the recognition of feelings of hurt and outrage. To take the high road, and to be praised for grace and class involves women, in particular, cowing down and suppressing thoughts and emotions that are perceived to be too masculine. In her speech, Adichie presents this very issue as a barrier to gender equality when she states: When we think about feminism, what it means to be a feminist, and the history of the feminist movement, we automatically slip into the “us vs. those other” or them” mentality. Our minds immediately consider the work that has been done, and has yet to be done, by us women to address the wrongs in society that has been created by those men. As women, we become fixated on tearing down the restrictions placed on us by patriarchal society. Yes, this particular aspect of feminism is indeed a very necessary step to establishing gender equality. But perhaps even more heinous than the sexual, economic, social, and political restrictions men place on women, are the restrictions women place on themselves in the same areas by the mistreatment of each other. As women, we must be just as committed to addressing this kind of injustice if we are going to continue to make strides towards gender equality. Feminist: A person who believes in the social, political and economic equality of the sexes. Adichie adds to this definition with the idea that a feminist is a man or a woman who says, “yes there’s a problem with gender as it is today, and we must fix it, we must do better. The take away from this particular Grammy’s fiasco is that the process of fixing the gender problem involves, first and foremost, us women a much better job in the way we treat each other. By S. Rae Peoples

Originally Posted on LinkedIn on November 25, 2014 Yesterday I had my son watch the news with me, focusing on both the boy that was shot in Ohio, and Michael Brown, Jr.'s untimely death. He asked questions. I answered. He had words. I listened. I used these events as talking points and lessons for my son. Like the importance of following directions. Like why I do not buy toy weapons. Like how his actions and the choices he makes can literally be a matter of life and death for him. And how even when you make the 'right' choices, and take the 'right' actions that you think will preserve your life- the truth is that because he is a Black male, his life can still be snuffed out. He asked sweetly, "Why Mama?" And I gave him the truth: "Because there is no sacred regard for just how precious and beautiful your life is..." These are the lessons I push for my son to understand. I have to. His life really does depend on it. It's a tug of war: pulling to teach him things so he can hopefully somehow increase his chances of survival. I find myself thinking more and more lately, "I just want him to live and see his 16th birthday. I just want him to graduate..." No mother should have to entertain such thought. And yet, against this pull to teach survival skills to my son, I find myself pushing up against this ridiculous duty of mine. Ferociously resisting my having to eek out a bit of his sweet and innocent childhood with every "lesson" our society reminds me to teach him. I mean, he's only 9 years old for crying out loud! The back and forth, push and pull, up and down of it all is so exhausting. On so many levels. It is both tremendously sad and taxing for both me and my son. Emotionally, spiritually, physically, socially, and mentally. All of the things. And as if that aspect wasn't enough, I always find myself getting so pissed off at my white counterparts. I have anger and resentment. It undoubtedly stems from a level of jealousy. I am jealous because they get to raise their sons in a wonderful bliss of ignorance. They don't have to teach their beautiful sons how to hopefully survive to their 16th birthday. That luxury and right just is a given for them. Their sons can play and explore and fall down, and fail confidently and free from fear of dying at the hands of their justice system. Their sons bask and play in the innocence of a childhood that doesn't have to be soiled by the "Dos and Don'ts to Save Your Life" rhetoric that I give my son every.damn.day. I want that for my son. I want him to have an innocent childhood. I want him to know that he will live to succeed and fail and love. I want him to have the confidence that comes from such security. I want him to not just think of "My Life Matters" as a cry for help and justice, but as an affirmative statement. I want him to see those words as a reality, not just a possibility. But I can't have all this for my son. And that's why I'm pissed. Apparently a mother's anger isn't enough. The anger of a community doesn't seem to be enough either. It's going to take more than this. It's going to take mother and fathers from every community getting angry with us. It's going to take every community realizing that the Black community is their community. And it's going to take these communities getting agitated beyond retribution at the ways in which life is being trampled upon, disrespected, and pushed to the point of damn near extinction. It's going to take more of us realizing just how intricately connected we are. I am you. You are me. Your child is my child. My community is your community. It's going to take more of us understanding that there is no distinction. There is no him versus her. There is no I versus he. There is no us versus them. There is only Just. Us. By S. Rae Peoples

Originally Posted on LinkedIn on November 7, 2014 Still reeling from the huge Republican sweep in the midterm elections, I got hit with yet another bizarre reality of the election on Wednesday night. While listening to a commercial on MTV, I hear the words, "78.7 % of Millennials did not vote in the 2014 midterm elections." Responding to what clearly had to be erroneous information, I found myself yelling at the T.V., "Wait, What? Did I just hear that right?..(chuckling) that just can't be true...." But it was true. And apparently, MTV was just as astounded as I was on this matter, as they (in the same commercial) launched the #WhyIDidn'tVote campaign to illicit feedback from Millennials so as to attempt to understand just what the hell was going on with this group on election day. Personally confused and concerned about this, I decided to do a bit of my own research, starting with my own family. In a family that prides itself on being politically savvy and engaged, the absence of a generation during a political exercise sparked a myriad of reactions, particularly between the millennials and the Gen Xers in the family. Being a Gen Xer myself, I completely understand the sighs and side eyes my cohort is quick to throw to Millennials for not showing up at the polls. From the argument of "our ancestors died so that we could vote today" (completely valid), to don't vote/don't complain quips (equally valid), it's clear we GenXers feel some kinda way about the absence of Millennials at the polls this past Tuesday. However, before we declare Millennials as a detached, self-absorbed, and politically obtuse generation, let's be clear here: Milliennials are a political force to be reckoned with. They have a history of coming to the polls in droves. When they do show up, they show out, speak up, and affect change with an unparalleled fierceness (refer to the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections). With so many refraining from flexing their political muscles, during the midterms this year, I couldn't help but think that there is a crucial lesson and warning that is rooted in their (in)actions. My conversation with some millennials revealed that much was said in their peers not participating on Tuesday. Here are some key points from the conversation to consider:

In addition to these points, for Millennials who identify as Black/African-American, voting to respect the struggle of ancestors who fought for the right to vote, will always be important. However, it has been pointed out: "We fully understand our responsibility to vote because our ancestors fought for us to vote. And yes, this is an important aspect, but that does not negate the need for us to be able to believe in what should drive us to the polls." For the Black community, it is true that not voting when you have clarity on who you want to support, and why, is certainly an affront to the fight of those who came before us. However, the other side of the coin, and just as egregious, is voting knowing you don't support any candidate, just to say "I voted." In the end, our ancestors fought not so we would have to vote if we felt no conviction to do so for any candidate. I would offer that they fought so that we could have the choice to vote. After my discussion with my family, I'm convinced that that MTV (and the rest of us) got this all wrong: Millennials actually voted. It was a vote of no confidence in the political trajectory of our nation. As one millennial stated: "If a no vote could count, no one would have won. If there was a "vote of no confidence" option on the ballots, that would have been great, because many people, not just millennials would have chosen that option. But that isn't an option, and I'm not going to vote without having confidence for either side just for the sake of voting." In all honesty, the confidence of Millennials in our political system has been deteriorating since 2008. According to a report in Time: Obama won 60 percent of the 18-29 vote last November, but that was down six percent from his victory in 2008. More worrisome for Democrats was that according to new data from the Census Bureau, youth turnout dropped precipitously between 2008 and 2012, from 51 percent of eligible 18-29 year olds to 45.2 percent.Clearly, with their dwindling political turnout the past few years, Millennials have been trying to convey a very profound message all along. We just haven't paid attention to it, until now- when basically 80% of an influential population in our society refused to engage on Tuesday. Whether we think Millennials should have gone to the polls, at this point is really inconsequential. We could reprimand and scorn Millennials until we're blue in the face, and at the end of the day the fact will remain the same: they didn't show up. While we don't necessarily have to agree with the sentiments and opinions outlined here, we have to realize that there are Millennials who feel this way. With this realization in mind, it would behoove the DNC to listen to the excruciating loud silence of a generation that placed them in office, learn the lessons to be had, and adjust its strategy, if it plans to gain any kind of momentum for 2016. By S. Rae Peoples

Originally posted on LinkedIn on September 29, 2014 Recently, in becoming more intentional about the way I "look" not just on the outside, but also on the inside, I've started practicing various forms of yoga. I have been surprised at the short amount of time in which I've been able to experience the positive mental, physical, and emotional effects of yoga. Fearing that this near immediate advantageous impact was just my being enamored with a new physical activity, and giving yoga more credit than it's worth, I looked at some of the research out there on the benefits of yoga. One of the most intriguing facts I found in the research is that although aerobic exercise such as walking and running, greatly increases our brain's performance, Dr. Neha Gothe, in a recent article in Women's Health maintains: "...unlike the benefits of aerobic exercise, which take a while to kick in, yoga has a pretty immediate effect on your mind-so you'll feel it just 30 minutes after you say "Namaste." Apparently, the expedient benefits of yoga I've been experiencing are not a muse, or just the "honeymoon phase" after all! these benefits have transferred over to an enhanced performance in my job as a student affairs professional in three specific areas: 1. Creativity I'm sure many of you can relate to my struggle here: I'm in the office, working on a project, in my zone, and getting sh%t done like a boss!... then out of nowhere-BOOM! I run straight into that creative block. It's literally as if the creativity clock ticked its last tock. At this point, I'm fresh out of ideas, words, and thoughts. I have absolutely nothing left to give. For me, getting over this block was the worst. Oftentimes, I'd give into the block, take my loss, and just call it a day on whatever I was working on, being forced to come back to it at a later time (which usually meant between 2-4 days...sometimes even longer). I assumed that by practicing yoga that I would no longer have a problem with creative blocks. That wasn't the case. However, though the creative blocks still come, I have noticed that the period of creative productivity (the time before I reach any block) lasts longer, and when I do hit those inevitable blocks, yoga techniques such as focusing on my breathing, stretching and meditating (even if it's just 5 minutes) helps me to push through the blocks much quicker than 2-4 days, in fact, I am able to get back into my zone that same day, instead of prolonging the project any longer than it needs to be. 2. Focus & Stamina Confession: I have attempted, and fallen out of at least 55% of my asanas during any given yoga session. To this confession, I should also add that my attempts and falls have been anything but graceful. In fact, more often than I really do care to count, my clumsiness and frustration have reached new heights with every class. For me, I've found that whenever I have fallen out of position, it has been right after I've allowed my mind to wander to things like, "What am I going to have for lunch after class", or "I wonder if I remembered to turn off the stove before I left this morning..." However painful and embarrassing this lesson may be, I am learning that there is an intimate relationship between my being present in the moment, and my ability to be focused, and get through the physical and mental challenge of each posture. In order for me to pick myself up from my mat, and get back into position, I have to let go of my ego, and clear my mind from thoughts on the past or future. I can't be in the past, I can be in the future. I have to be in the present. The ability to be present in the moment supports my ability to prioritize tasks and focus on what I need to accomplish at work, in any given part of my day. When I begin my workday, I now make more of an effort to keep my mind clear of thoughts of the "woulda, coulda, shouldas" of the past. I also commit myself to not being bogged down with what I think awaits me in the future. Instead, nowadays, all my energy is directed to my here and now. I become involved only with present tasks that need to be addressed. With such clarity of mind and a pool of energy that is not spread so thinly all over the place, I complete tasks much more efficiently, and projects are completed with a higher degree of care and genius. 3. Patience & Empathy My yoga sessions have provided me with the physical and mental space to understand and accept myself. With nothing to feel but my sweaty limbs, and nothing to hear but the rhythm of my breathing, I have become more aware, and accepting of my shortcomings. I am developing a deeper understanding of my own sensitivity, and I have come to appreciate the inherent respect I deserve as a human being. Transferring this particular aspect to my job, it has become increasingly easier for me to see my colleagues, and students in the same way. The dignity, light, and potential I recognize in myself, I now recognize in others around me. This recognition enables me to extend to others the same amount of patience and care that I give to myself. Engaging with others from the foundation of acceptance, patience, and empathy allows me to create and maintain more positive relationships with my peers and students. Ultimately, I've come to realize that yoga is so much more than successfully executing an asana. In learning how to get into, and hold each posture, you learn more about yourself. In your journey through yoga, you become transformed, and your transformation adds value and meaning to those around you. Whether those around you are at home, or at work, this value and meaning we give to others is, in my opinion, the true study of asana. Namaste. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed